By Quincy Abramson, UNH Italian Studies & International Affairs Program | JUNE 2017

My maternal grandparents used to live on the beautiful Lake Damariscotta in Maine, and my whole extended family traveled to Damariscotta every Fourth of July to play horseshoes, grill, go boating, and swim. My cousins and I usually swam in the shallow water off a small nearby point, but sometimes my uncles loaded us onto the boat to explore the deep, dark middle of the lake.

One day, when I was about 5 years old, I hesitantly jumped into the blackness. As I came up for air, I found myself face to face with a foreign and terrifying creature. I quickly paddled back to the boat to tell the story of my encounter with the killer lake shrimp.

Fifteen years later, my family still makes fun of that story, which they believe is a product of my fantastical childhood imagination. But my memory is vivid. How could I forget seeing a semi-translucent, alien-like shrimp, in a lake of all places? Recently, I went searching for the truth.

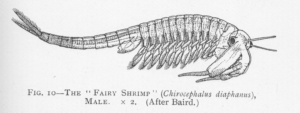

Through the course of my Internet research, I placed a call to the Maine Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. I recounted my story, and one of the biologists promised to send me an article that might solve my mystery. I was so excited when I opened the article and saw a picture of my monster! My 5-year-old brain had inflated the creature’s size, but now I know that years ago I was face to face with a fairy shrimp!

Fairy shrimp are tiny freshwater crustaceans that grow to a maximum length of 4 centimeters. They thrive in cool, fishless environments, and are generally found in vernal pools for a brief period of time in early spring or summer. Fairy shrimp aren’t great dispersers, so their movement across the landscape occurs by wind or water dispersal, or by hitchhiking on the legs of more mobile animals that move between ponds.

Female fairy shrimp lay two types of eggs: a soft shelled summer egg from which juveniles hatch and mature during the same season and a hard shelled egg that will remain in the icy, dry pool bed until the following spring. Their eggs can stay in a dried pool for years until the juveniles unexpectedly show up in late winter or early spring, earning them their magical name.

Fairy shrimp are important indicators of good water quality. Their presence qualifies a vernal pool for protection under the Maine Natural Resources Protection Act. Fairy shrimp are Federally threatened because we continue to lose vernal pools, and so the presence of fairy shrimp is special.

Somehow, I had encountered a stray adult fairy shrimp, against all odds, in a deep and fish-filled lake. And while the killer lake shrimp of my childhood was petrifying, fairy shrimp (as I know them today) are ethereal and fill me with nostalgia for my days spent swimming in the lake and building fairy houses on the shore.

Like many other states, Maine must continue to protect the fragile vernal pool communities. We need to reduce the amount of pollutants that run off into streams, wetlands, and coastal waters. Even in a beautiful and wild place like Maine, local pollution and climate change have severe impacts on our aquatic species, including the delicate fairy shrimp. Simple changes like reducing road salting in winter, maintaining healthy riparian zones, and cleaning up litter can make a huge difference for vulnerable species.

Although my first impression of fairy shrimp was not particularly pleasant, I have come to love these tiny crustaceans. And if we all do our part to reduce our environmental footprint, maybe our kids will swim with fairies too.

References

Ward, M., & deMaynadier, P. (2009). Fairy Shrimp: Coming Soon to a Wetland Near You? The Maine Entomologist.

Vernal Pools: Vernal Pool Invertebrates. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. http://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/VernalPool_Invertebrate.aspx

Quincy Abramson is currently pursuing dual majors in Italian Studies and International Affairs, as well as a minor in Art History, from the University of New Hampshire.

Quincy grew up gardening and raising chickens with her mother and grandfather. She attended Audubon camp throughout her childhood, and later worked as an assistant counselor. Quincy is a self-proclaimed ‘fish out of water’, desperate for any chance to swim, especially in lakes and rivers. All this time spent in nature, has contributed to Quincy’s love of New England’s forests and waterways, and her desire to protect them.